If we were able to see people in other countries and learn about our differences, why would there be any misunderstandings? War would be a thing of the past.

Mick's musings

Sunday, September 7, 2025

Who Invented Television?

If we were able to see people in other countries and learn about our differences, why would there be any misunderstandings? War would be a thing of the past.

Monday, January 27, 2025

Legalized piracy -- the tale of the Snap Dragon

|

| Decal created by Sharon O'Connor for her sailboat named for a legendary privateer |

The two previous pirates I wrote about are joined by many others who made life miserable on the eastern coast of Canada during the Golden Age of piracy -- from the late 17th century to about the middle of the 18th century. I picked the particular duo because of the horrible death and after-death of the one and the horrible life led by the other.

But I've had a request to tell the tale of one of the most successful privateers of the 19th nineteenth century -- Otway Burns, a North Carolinian who raided shipping from South America to Newfoundland until his ship, the Snap Dragon, was captured off the shores of Newfoundland in 1814.

Burns was born just before the Revolutionary War, though the exact date seems to be uncertain, and lived to the middle of the 19th century and was a native of North Carolina. During his 70+ years, he worked as the captain of a merchant ship, harassed British shipping during the War of 1812, built a successful business empire, and served as a state legislator. He married three times, each of his wives preceding him in death, and had two children by his first wife, a son, Owen, and a daughter, Harriet. [1]

His career as a merchantman captain came to an abrupt halt with the commencement of the already mentioned war. With a partner, he purchased a small ship, outfitted as most merchant ships were, with minimal armaments. They renamed the boat Snap Dragon, sometimes referred to as Snap-Dragon, and applied to the U.S. government for letters of marque. Upon receipt of the documents, they sold shares in the ship to investors.

For the uninitiated, letters of marque are issued by governments authorizing captains of ships to harass and capture foreign shipping, usually during times of war. Captured ships would be taken to a nation's ports, the circumstances of capture reviewed, and if the capture passed muster, sold along with whatever cargo they carried at auction. The government often took a share of the money, with most of the proceeds going to the captain and crew.

Now, you also need to know that letters of marque are enshrined in Article 1 of the American Constitution. The practice was outlawed by international treaty in 1856. though technically the U.S. still has the authority to do it.

Captains so authorized, and their ships, are called privateers, and they served the purpose, especially for America, of expanding and supplementing the nation's naval presence. Not everyone was on board with the concept, though.

When Burns sailed into port in New Bern, NC, he began recruiting crewmen. Local political leaders who believed privateering to be glorified piracy would find out who the recruits were and lend them money. Once indebted, the crewmen would be arrested for being in debt. If you don't have enough crew, you can't sail, and you can't terrorize British shipping. These local pols may have been leftover British sympathizers.

Warrants were issued for the arrest of crewmen who had returned to the ship,and a group of constables were dispatched in a boat to arrest the debtors. Burns ordered his men to overturn the boat, and the constables were forced to swim ashore. A lawyer then began stirring up trouble and called the ship, its master and crew licensed robbers. When Burns heard of this, he rowed ashore, thrashed the lawyer and threw him into a nearby river.

The Snap Dragon and its crew made three long voyages, sometimes cooperating with other privateers, sometimes going it alone, even if not always intentionally. Burns and his crew accounted for upwards of a hundred captures, though the exact number is unknown because some of his logs has been lost.

Some of the captured ships would be retaken, but the prize amounts for the ships sometimes reached into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and in a couple of instances, more than a million. I can't say whether the numbers cited by his chroniclers are adjusted for inflation, but I don't think so. After all, the book's contents are less than 100 years removed from the events.

Burns' range extended from near the equator in South America, through the Caribbean, along the eastern seaboard of the U.S. to the maritimes and Newfoundland in Canada.

He fearlessly attacked ships that were larger and much better armed than his. Sometimes his gambit paid off, sometimes he was forced to retreat. In one incident noted in his logs, he attacked a much larger British naval ship that had tried to pass itself off as a merchantman. The battle raged for hours and only ended after the British ship managed to carry off Snap Dragon's bowsprit, which led to its foremast collapsing. Burns commented that had the ship not lost its bowsprit, he was certain he'd have won.

His primary strategy, as I understand it, was to pick a target, sail for it until he caught up to it, and ram it. His crew, which was much larger than needed to actually sail the ship, would board the enemy ship and overpower its crew. Burn's crews could be as large as a 100 or more men, and most of the merchant ships would have from 20-60 men.

During the ship's last tour, Burns' health diminished to the point he relinquished command to one of his officers. (I have more than one name for the officer, so I can't say who it was with certainty.) The British had disguised one of their ships as a merchantman in another effort to trick the Snap Dragon's crew and took up a position off Halifax.

This time the ruse worked. Snap Dragon took an initial broadside, and though she was much better armed than usual, she was no match for the British ship. Her substitute captain was killed and many of the crew wounded. The remaining crew struck the ship's flag and surrendered. Ship and crew were taken to England, where the crew was imprisoned. No one really knows what happened to the ship.

Much later Burns built another boat and named her Snap Dragon, She was a much smaller boat that featured an innovation called a center board. For non-sailors a centerboard is, well, a board that extends through the, um, center of the ship's hull. This substitutes for a keel and makes the ship better suited for sailing in shallower waters.

And more than 100 years later, my wife had a small sailing craft with a center board that she named Snap Dragon.

[1] For this post, most of the information is summarized from the contents of the book Captain Otway Burns, Patriot, Privateer and Legislator published in New York in 1905. This is a collection of materials compiled by one of Burns' descendants and is available through the Library of Congress, Google Books and Internet Archive, among other outlets.

Wednesday, January 22, 2025

How bad do you have to be?

|

| Replica of Ned Low's pirate flag |

Edward Lowe, aka Ned Low, became so reviled by his enemies and chroniclers that you might say he was considered loathsome, a description that became part of his nickname. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle mentions Low in his book The Green Flag, grouping him with other brigands and describing them as capable of "amazing and grotesque brutality."

The English Wikipedia entry for Low quotes The New York Times as saying "Low and his crew became the terror of the Atlantic, and his depredations were committed on every part of the ocean, from the coast of Brazil to the Grand Banks of Newfoundland."

A children's book on pirates written by Howard Pyle said "No one stood higher in the trade than [Low], and no one mounted to more lofter altitudes of bloodthirsty and unscrupulous wickedness." Pyle went on to wonder why Low had not received the attention of pirates such as Blackbeard (William Teach), Black Bart Roberts and other contemporaries of the age. Like that was a bad thing.

He sounds pretty bad, but just how bad do you have to be to earn such scathing disapprobation? Pretty bad, it turns out.

Low began his life as a scoundrel at a young age, according to some of the early sources on his life.Thievery, gambling and grifting were his trade in stock. He and at least one of his brothers practiced their felonious craft in the Westminster part of London. Bucking him would be an occasion for a thrashing.

Eventually, though, he signed onto a merchant ship and made his way to the colonies where, after a time, he settled in Boston, MA, obtained a job as a ship rigger, married and had children. He and his wife actually attended Second Church in Boston, where they had their children baptized.

After the death of his wife from complications of childbirth, he entrusted the newborn girl, their third child, to his in-laws and left to do other things. He first obtained a position on a sloop that was slated to pick up a cargo of logwood, a particular species of tree apparently.

While loading the wood, he and some crew members decided to return to the ship, arriving around chow time. The captain wanted them to return, but Low suggested they be allowed to eat before returning, an offer that was countered with the proposal that they have some of their ration of rum and get back to work so the ship could leave before attracting unwanted attention.

Low's responded angrily, grabbed gun and tried to shoot the captain. He missed but hit another crewman. Ned and his cohorts ran off with one of the sloop's boats. The next day they commandeered a larger vessel and began their life of piracy.

They ran down to the Leeward Islands and the Caribbean, capturing ships to add to their fleet, burning others to the water, and threatening the ships' crews -- join us or die. His reputation grew until all he had to do was show up, set his pirate flag, and their prey would surrender without a fight -- for the most part.

Several tales are told of his encountering recalcitrant captains whose resistance would meet with loss of various body parts, mostly facial, before being executed. One particularly gruesome incident involved a captured ship's cook, whom the crew decided was a greasy fellow. Think about cooks and grease, and you may figure out what happened to him.

Low seemed to be solicitous toward English ships and would avoid plundering them if they were clearly British, and also, probably because of tenderness for his wife and daughter, would free women and children before pillaging a ship, seemingly his only redeeming character traits.

At some point, Low turned his sights to American shipping, attacking and burning boats from Massachusetts -- just because their crews were New England men -- doing the same to a Connecticut ship, letting go a ship from Virginia after its crew relinquished the cargo, and co-opting a Jamaican ship.

More American ships fell to Low's predations all the way up to Maine. From there he headed to Newfoundland (at last we get to Canada!) As he and his crews approached St. Johns, they thought they spotted a large ship suitable for taking in the foggy harbor. But on hailing a passing ship, they learned the ship was a British naval vessel. This prompted a retreat from the harbor and a continuation north, where they plundered a village and harassed shipping.

Low's time in the area gave rise to a rumor that he and his crew had landed on an island in the Bay of Fundy, which abuts Nova Scotia, and buried some of their loot there. Many people have searched over the years for the treasure -- which also sometimes is attributed in lore as actually being Captain Kidd's treasure.

One treasure seeker who visited the island in 1929 claimed to have found jewels and coins, though this was never verified. And another adventurer visited the island in 1952 and claimed to have found a skeleton along with silver and gold coins. He published photos in Life magazine, but the discovery has never been authenticated. Others have surely searched since so I'd not be booking a trip to Nova Scotia.

Karma may have caught up to Low a couple of times. He received a sword wound in battle once and had the ship's surgeon sew him up. But he was unhappy with the result and began berating the surgeon, who then struck Low's wound, causing the stitches to pull loose. The surgeon then left him to stitch himself back up.

You can find multiple accounts of the end of Low's career, so we don't know for sure what happened to him, but the likelihood is that he was captured, tried and executed. One of the capture tales provides a second possible karmic consequence. Low had been involved in a set-to with one of his crewmen and later attacked the man while he was sleeping. This prompted the crew to decide they'd had enough of Low's temper and violence, and they set him adrift.

Those who live by the sword ...

Sunday, January 19, 2025

Argh, matey. There be pirates here, eh

|

| Depiction of Edward Jordan's fate as a convicted pirate |

When most of us think of pirates wreaking havoc on the high seas, I suspect that we imagine the brigands of Stevenson, or the swashbucklers played by Flynn, or in more modern times, the quirky characters from Pirates of the Caribbean.

Wednesday, October 23, 2019

Wonderland

I knew from Google maps that our drive from Deer Lake to L'Anse aux Meadows would take us along the coast, so I expected some nice scenery. I had no idea what the road would be like, whether we'd find places to stop for breaks, or how much traffic we'd encounter, though I suspected the answer to the traffic question would be "not much."

We picked up Highway 430, which would take us most of the way to our destination, just outside the airport and began our journey. The rental company had graciously given us a free upgrade (or else they didn't have anything else on the lot), so we were ensconced in a nicely appointed CUV instead of the much smaller sedan I'd picked.

|

| Flowers Cove, one of many villages along the coastal drive to L'Anse aux Meadows. |

If you look at a map of Newfoundland, you'll see that the island is shaped like a mitten, only with an exaggeratedly long thumb, known as the Northern Peninsula -- an apt but somewhat unusual name given that the island has four other peninsulas, none of which are named Southern Peninsula.

We would drive about 40 km (about 26 miles) northwest before reaching an inlet off the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where we spied our first water, and then another 20 or so km before the road bent to the northeast along the coastline. Looking at a map again, you might think you'd be in sight of the water until you turned inland for the leg to L'Anse aux Meadows, but you'd be wrong.

Instead you alternate between being very close to the shore and having the road take you into the middle of evergreen forests, which a Candian government website informs me are mostly types of fir trees. The journey took us through a portion of Gros Morne National Park, through which run the Long Range Mountains. The park is home to the island's second tallest peak, Gros Morne, at 2,648 feet. On the way out we knew we were in mountainous territory, but we were often driving downhill. The return trip afforded us a much better view of the range and impressed us with its size and beauty.

As I said, we'd drive through a bit of forest, then jog toward the coastline, with gorgeous vistas of water, often dotted with islands, that would elicit the appropriate verbal appreciations. Eventually, the forest gave way to lowlands dotted with numerous ponds.

Because it had been rainy, we couldn't tell which of the smaller ones were more or less permanent and which were just low spots filled with the recent rains. But larger ponds, some big enough to be called lakes back home, were scattered about as well. The largest of the ponds show up on the map we had, with names such as Parson's Pond, Portland Creek Pond and Western Brook Pond. One lake, smaller than some of the ponds, is called River of Pond Lake.

Our highway comprised two lanes, and the speed limit was 90 kph (56 mph) except when traveling through villages, which we did. A lot. Then the limit dropped, most of the time, to 50 kph (31 mph). I began by scrupulously obeying the maximum posted limits because I didn't want to be stopped by a Canadian police officer. I had no idea whether they issued warnings. Turns out that wasn't a problem. We never saw a police vehicle on the trip there and back.

Most of the Canadians (I assume, unless like me, they were U.S. tourists driving rentals) drove much faster. I matched speed a couple of times, and found they drove about 110, close to 70 mph. I eventually settled into driving at 100, dropping to the proper in-town speeds, which most everyone seemed to obey.

|

Flowers Cove, closer view. Note the simple construction of most of the buildings. The

church features a steeple, an unusual sight in most of the towns we passed through.

|

We passed through numerous towns, all, according to our map, of 500 or less population. The towns pretty much followed the pattern of wherever a cove with a decent beach was, a town was. In one stretch of about 100 kilometers, we passed through or very near 18 towns, some so close to each other that we might see a 90 kph speed sign and almost not have enough time to hit that speed before slowing for the next town. Most of these tows had "cove" in their names: Blue Cove, Black Duck Cove, Pigeon's Cove, Deadman's Cove, and my favorite, Nameless Cove, among them.

A ferry stops near Pigeon's Cove, so large it almost looks like a cruise ship. This ferry runs between Newfoundland and Quebec, quite close to the Labrador border.

About two-thirds of the way, after passing the last of the coves -- Eddies Cove -- the highway curves toward the interior of the peninsula, where we saw acres upon acres of fir trees, like so many perfect Christmas trees. I wish I had developed my poetic side so I could adequately express how captivating this drive along the coast is. Or perhaps that I had not forgotten the spare battery and charging cable for my action camera and had used it to record parts of the drive so you could see for yourself.

The houses in all these little villages were mostly made in what is known as cracker-box style - one or two story rectangular boxes with gables roofs. Occasionally you might see a house built in an "l" or a "t," but those were just two boxes fitted together. The ones nearest the coast usually stood on stilts, and most of the time the only way to distinguish one house from another was its color. White was very popular. Churches followed the same pattern, and the presence of a cross on the end of the building served to distinguish them from a large house or a shop of some kind.

During both legs of the trip we encountered light rain and fog, with occasional outbreaks of the sun, but the fog along the coastline was worst on our trip back to Deer Lake. We slowed down, but given the amount of traffic on anyone section of the road, we were in little danger of running up someone's tailpipe unawares.

We encountered some road construction, but the worst of it, a cut-down to one lane, was controlled by a temporary traffic light, not flagmen. On our way out, the light on our side wasn't working, so we had to wait until we didn't see anyone coming before proceeding. Not that this was a problem. No traffic stacked up behind us, and we had plenty of sight line to give us confidence. The light on the return worked just fine.

Traffic picked up measurably as we neared Deer Lake, but it wasn't anything like driving at home. We had time to kill before returning our car and catching our flight, so we decided to grab a bite to eat. We tried a Tim Horton's near the airport, but their electronic menu boards were down, and the woman who tried to help us was a very nice woman who did not speak English as her first language. She must have been new because she didn't know the menu, and when we asked what they had, she referred us to the electronic menus. We tried to communicate for a short time but gave up and went somewhere else.

At the airport, our flight was delayed by about an, presumably because of a rain storm that blew through No PA announcement was made, and we only knew about the change because I looked at the flight board at the gate and noticed the departure time had changed. Even then, we wound up leaving later than the posted time.

The mall claims it has 140 stores, and construction was underway to expand its capacity, not something you see a lot with American malls. We didn't recognize any of the chains stores, except in the food court, where we knew one or two of the places, but I can't recall which ones they were. After a bite -- Chinese food that was pretty good for a mall cafe -- we returned to the hotel and settled in.

Some random observations:

Say What?

Like most places, Newfoundland has its share of unique expressions. We didn't hear any of them, except for the one waitress who called us "m'dear" or "m'dears" all the time. That might not seem so different from the "dear" or "dearie" or "hon" you hear often in this part of the woods, but she had a bit of an accent and a cheery manner that made it seem charming none the less. I tried out what I had read was a oft-used greeting, "Whaddayat," basically "what's up," and only received laughs in reply. Must have sounded to much like a tourist. If you'd like to hear some other expressions , YouTube has plenty of videos about the subject, but I like this one best: Newfoundland expressions

Canadians are so polite ...

... even the panhandlers are nice to you. A few hit me up in downtown, and when I apologized and said I didn't have any cash with me -- which was true, by the way -- they usually responded with, "Oh, that's OK. Thanks."

Yummies

St. John's is a blend of the old and the modern. Much of the town north of downtown looks like any suburban town just about anywhere in the U.S. Of course that means you run across your share of chain stores, most of which you've never heard of. They do have Circle K, with all the soda selections you recognize, though they are big on ginger ale as well. Two of the most ubiquitous chains are the fast-food places Mary Brown's Chicken and Taters, and Tim Horton's.

Tim Horton's wins hands down for the number of restaurants, though. If they are smaller places, they pretty much just serve coffee, pastries and breakfast sandwiches. The larger ones also advertise hamburgers. We had muffins and soft drinks, sold in the metric equivalent of 20 oz. bottles, there a couple of times, but nothing else. We ate at a Mary Brown's one time, basically it's not-bad fried chicken sold with what we would call cottage fries. OK, but nothing to write home about.

I had intended to try a Canadian dish called poutine, but never got around to it. It's fries covered in gravy and cheese curds. A search on Google shows poutine to be available in the Metroplex, but I didn't spend anytime looking at menus to see if this is true.

Gassing Up

I had to buy gas a few times during our stay. In the Northern Peninsula I paid C$2.27 a liter, which works out to almost US$7 a gallon, if I did the math right. In Deer Creek and St. John's, gas cost about C$1.25 a liter, or something close to US$3.80 a gallon. Good thing we drove cars with high gas mileage.

Coming Home

We flew into and out of Toronto, which was our major connection point for the flights to an from St. John's. Going through customs when entering the country was a breeze, and with three hours layover time, quite stress free. The agent who checked us through looked like someone out of central casting in Hollywood. Blond, good-looking, obviously fit. He ignored me completely when I remarked on that fact to Sharon.

But Toronto is a port of entry on the way back. I'd scheduled our departure for Dallas to be just an hour and a half after our arrival, which should have been plenty of time if all the flights were on time, and they were.

We thought we'd head over to our gate, grab a quick bite for lunch and wait for our flight. But we had to go through security, and not the kind of internal security for flights within country. Nope, this was full-on go through customs, then face a TSA style security check. On top of that, my ticket was marked for a random full security check. And with what seemed like thousands of people who needed to be process, I became worried about time.

I thought my screening would take much more time than Sharon's, but she got stuck behind some yahoo who needed extra attention, and we wound up clearing security at about the same time. A check of the clock showed us we'd need to hustle to make our flight. As we entered the corridor leading to our gate, we heard a last-call announcement for our flight along with our names. We broke into a trot and managed to board, but we've never cut a flight that close before.

Moral of the story: Make sure you know if you're passing through a POE, and leave plenty of time to catch your flight.

|

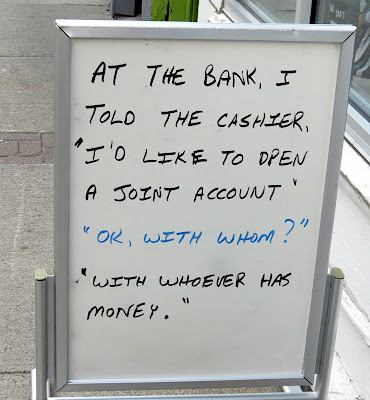

| Humor outside a shop. |

Tuesday, October 22, 2019

Leif Erikson slept here -- maybe

|

| Sculpture of Vikings welcomes visitors to L'Anse aux Meadows |

I planned this trip with nothing more in mind than visiting St. John's. But as I researched things to do, I came across a mention of a Viking village recreation that other tourists found interesting. Because the site often appeared in conjunction with St. John's, I thought it must not be far away and suggested we should check it out.

|

Unidentified cruise ship anchored in the cove near L'Anse aux Meadows. It

left while we toured the site, so none of our fellow tourists (probably) had

come here on that ship.

|

I checked Google Maps for driving directions, and it told me the attractions were almost 1,100 km away -- about 664 miles -- and the trip would take more than 11 hours to drive. Now, I've driven that far in a single day but -- for one exception, a trip to South Padre Island -- I was a lot younger then. We'd have had to split the trip up, meaning the trip would take four days out of our planned seven-day trip.

|

The visitor center overlooks the site. You can just see the sculpture on the

hill behind the building.

|

We picked up our car in Deer Lake and headed out. Our route would take us up the western coastline, through the edge of Gros Morne National Forest and Park, and east across the northern part of the peninsula. The only hotel with an available room I could find to book operated a multiroom log cabin in the woods -- charmingly called Viking Inn -- about a 30-minute drive away from L'anse aux Meadows. Fortunately it was sort of on the way, so we stopped there, checked in and headed for the site.

The site dates to about 1,000 C.E. Archaeologists believe it was primarily used as a repair station for Norse ships exploring the area and doing some trading, and that it was only occupied for a short period. The buildings were probably burned when the site was abandoned.

|

| This circular mound may be the remains of a hut for servants. Yeah, kinda small. |

The visible mounds mark the outlines of eight buildings, two halls that would have been occupied by a community leader and someone of high social status, a couple smaller living quarters for lower status members of the community and servants, another hall that may have housed laborers and three huts for workshops and a furnace for smelting ore to produce iron.

|

| If I'd had a drone, or longer arms, you could see the room divisions better. The hall above had four rooms. This one encompasses six or seven rooms. |

At the "back" of the park lie several recreations of buildings constructed using wood framing and peat blocks, the material that would have been available to the Vikings. The walls were at least three feet thick, and the roof was covered with grass. The day we were there, the temps were in the 50s, with decent wind blowing and mist/light rain falling, making it a cold, blustery day. Inside the buildings, an open fire and the natural insulation provided by the peat block made the building pretty cozy.

|

| Fake Viking. |

Inside the long hall, a couple dressed like Norse of the period discussed what daily life was like, and tourists were free to roam around the rooms. One large room contained recreations of Viking helmets, swords, axes, shields and the like, and visitors were welcome to dress up and take pictures.Let me tell you, the large wooden shields are as heavy or heavier than the weaponry, which is plenty heavy, and those guys would have needed a great deal of strength and stamina to wield these items in a prolonged battle.

|

Meeting of Two Worlds sculpture. The one on the left represents a Viking

sail, and the one on the right is supposed to be a bird, representing indigenous

peoples

|

A feature in the park we passed through on our way back to the visitor center is a sculpture called "Meeting of Two Worlds," which is supposed to represent when the Norsemen came into contact with the indigenous people of the area. This is also supposed to represent a closing of a circle wherein ancient peoples migrated into North America from the west untold millennia ago and met more modern descendants of our ancient ancestors who had settled in Europe but had now migrated east to come into contact with the native culture. Take a look at the picture, and tell me if you get that.

With the weather as raw as it was, we retreated to the visitor center to see some of the artifacts that convinced archaeologists of L'Anse aux Meadows' heritage and a replica trading ship. Most of the artifacts from the site are housed in St. John's according to the guide from our tour of the site. That would place them either in The Rooms or at the university. We didn't see any artifacts while touring The Rooms and didn't visit the university.

Next: A little about our drive up the coast and a few observations.

|

Bedroom area in the long hall. It looked like about four adults could sleep here. This

is located at the near end of the photo above.

|

|

| The far end of the hall. The room containing the replica shields and weapons in the photo of me above abutted the main gathering room, and this room joined weapons room. Note the bed at the end. |

|

| Students from Memorial University in St. John's excavating an area near the mounds. We were told their time at the site would end soon, and they would return to start classes. |

Monday, October 21, 2019

Next stop Ireland

|

| Cape Spear from the water. |

Look up things to do in St. John's, and on most of the lists you'll find on the 'Net will tell you to go to Cape Spear and watch the sun come up. I can imagine that's great advice, and I actually thought about doing it. Unfortunately, we were often so tired that we slept until well after sunrise. I did manage to wake early enough one morning to catch a picture of the sun topping the mountains behind our hotel.

What's that you say? I could have set an alarm. Why, yes, I could have. But in the end, I'm glad I didn't. We used Google maps to find our way there, and the instructions were convoluted, to say the least. Even assuming Google was giving us the most direct and fastest route, you have to drive through the old part of town, where Google directs you to take what it generously calls roundabouts, which bear little resemblance to the roundabouts towns are so fond of trying to bring back in the states or to the ones we've encountered in other countries we've visited.

No, these roundabouts are more like the town squares you encounter in small, Texas (and I'm sure other states) towns where roads converge at the courthouse or a park built in the center of town and one-way roads ferry you to the road you need. Some of these St. John's roundabouts had been created by installing those large concrete barriers you see used in road construction to reroute traffic. The newer parts of town do have actual roundabouts, though.

You eventually arrive at the road that takes you to Cape Spear, which reminded me of the Kentucky backroads I drove on too many decades ago, going up and down, twisting one way then the next, often at posted speeds of 30 kph (about 19 mph) or less, signs Canadian drivers tended to ignore.

Given that I hate driving unfamiliar routes, driving in the dark, and driving twisty roads, the idea of combining all three so I could see a sunrise didn't appeal to me, and I was glad we'd skipped it. Later, a woman sitting in front of me on the plane was reviewing her trip photos, and she had some spectacular sunrise shots from Cape Spear. She also had some great shots of puffins along a shore, while we only saw the birds in flight. I was a bit jealous, but I got over it.

|

| Marker proclaiming Cape Spear to be the easternmost point in North America. |

This latter path is studded with signs warning visitors to stay away from the edges and be careful during dodgy weather because waves crashing against shore can come up high enough to sweep them to their doom. Cheery way to start a visit. I read later about a woman who'd ventured to close to the edge in June of that year, had fallen off and had to be rescued. That article mentioned that several people have died after falling.

|

Stairs lead to the "new" lighthouse. The sign in the lower left warns visitor's

of the risk of falling off the cliffside.

|

Anyway, as I mentioned in a previous post, Greenland belongs politically to Europe and most folks don't tend to think of it as part of North America. But geologically, the island is attached to the North American tectonic plate, making it technically part of the continent. But who wants to quibble with tourist marketing?

|

World War II bunker built into the hillside. From inside, a tunnel branches

off to the left leading to an exit near the stairs shown above.

|

We began at the lookout and started the climb to the newer lighthouse. Before we arrived there, we came upon a military installation from World War II. Two large guns had been placed there to guard the entrance to St. John's, and a bunker providing ammunition storage and quarters for soldiers on duty had been built into the side of the hill..

|

Gun emplacement, without the lifting mechanism to raise the gun above

the concrete wall in front of the barrel.

|

|

| A poster inside the bunker shows the gun with its lifting mechanism. |

The guns were placed behind large, concrete structures that hid them from view. They were mounted on risers that allowed them to rise about the concrete barriers and bear on traffic in the ocean. A circular track allowed them to be pointed wherever needed along the expanse from Signal Hill in the north all the way to the southern approached to the cape. The guns are displayed in place without the lift mechanisms. And yes, German U-boats had come close enough to the harbor to justify the gun placements

|

The original lighthouse. For some reason, I did not take pictures of the

interior where the lighthouse keepers and their families lived.

|

The entrance to the bunker from the guns leads to a hallway that exits on the side of the mountain, from which you can take stairs up to the second lighthouse, which was built to replace the original lighthouse. The original lighthouse served from 1836 to 1955, and its light, by then converted to an electric light, was placed in the new lighthouse. I believe this second lighthouse does not still operate, but I don't know for sure.

You'll notice in the picture that the lighthouse is square. The government built a lighthouse and then surrounded it with the square part, which provided living quarters for a keeper and his family and workshop space. The building is set up using furniture and equipment from the mid-1800s, all very familiar to anyone who has visited museums featuring items from the period. Because the building surrounds the lighthouse, the interior walls are curved.

Other buildings on the site were being renovated, so I'm not sure what their purposes were.

More of the sights:

|

| Looking back toward Signal Hill, which is the promontory to the left. You can almost see Cabot Tower. |

|

| The clerk who checked us in at the hotel specifically mentioned the red chairs at the cape as a good place to watch the sunrise. |

|

| Click this picture to see it bigger and you'll see numerous birds trailing after these fishing boats. |

|

| Sail northeast from the new lighthouse, and you'll arrive in Ireland. |